Varia de Commensuracion para la Esculptura y Architectura

Arphe (Arfe) y Villafañe, Joan de

Seville. En la Imprenta de Andrea Pescioni, y Juan de Leon. 1585–1587

Sold

The first edition of Juan de Arfe's very scarce, comprehensive and influential treatise, De Varia Commensuracion, signed by de Arfe at the foot of the title.

'The most comprehensive Spanish sixteenth-century work on sculpture and architecture is that by Juan de Arfe y Villafañe ... '. (Hanno-Walter Kruft).

Juan de Arfe y Villafañe (Leon 1535 - Madrid 1600) was the son and grand-son of artists, an accomplished sculptor, anatomically-trained artist, metal-worker and architect, not to mention a highly important and influential theorist. de Arfe’s first major printed work ‘Quilatador de la Plata, Oro, y Piedras’ of 1572, is a notable text on the assay of metals (in particular silver and gold) and the valuation and assessment of gems, however, it is this later work of 1585, the ‘De Varia Commensuracion para la Esculptura, y Architectura’, with its debts - acknowledged or not - to Leonardo, Serlio, Dürer and Vasari that ensured his enduring legacy as the ’Spanish Cellini’. Divided into four books, each again divided into sub-sections (see below), the ‘De Varia Commensuracion’ is an artistic and scientific tour de force that marks de Arfe as an emblematic figure of the Spanish Renaissance. Richard Ford described de Arfe as ‘the greatest artist of his family’ and ‘the Bezaleel of the Peninsula’ (after Moses’ artisan of the Tabernacle and overseer of the making of the Ark of the Covenant) and ‘the Cellini of Spaniards’.

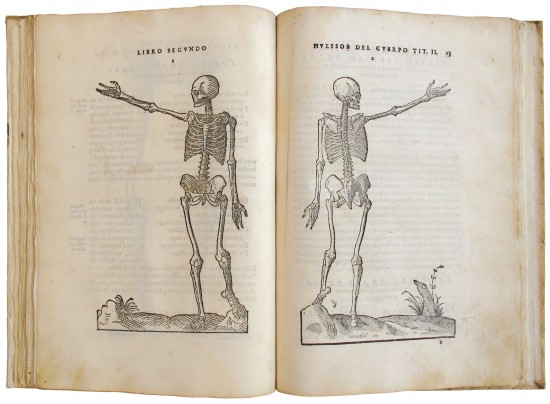

Each of de Arfe’s four books demonstrate his credentials as a pioneering Renaissance figure: his familiarity with the works of Euclid (translated into Spanish by de Arfe’s contemporary and friend Rodrigo Zamorano) is demonstrated in his ‘Libro Primero: Trata de las Figuras Geometricas &c.’, and his familiarity with navigation is demonstrated by a series of mathematical / navigational tables relating to Spain and her surrounds, astronomical instruments, their uses and so on. The ‘Libro Secundo: Trate de la Proporcion’ is indebted not only to Dürer and his ‘Hierin sind Begriffen vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion’ (1528) but also to the anatomical drawings of Leonardo. In a series of woodcut plates, de Arfe delineates the body, ‘representing outlines of the whole body or of single parts with the measurements’ (Choulant) including the body of a woman - de Arfe describes the essentials for a beautiful female body - and the proportions for a child. The affinities between de Arfe’s woodcuts and Leonardo are clear, however, what is less clear is their transmission. It is known that Pompeo Leoni acquired the majority of Leonardo’s writings and drawings, or at least those left to his father, Francesco, from Orazio Melzi in the 1580s while Leoni had a studio in Madrid. Leoni, working for successive Kings of Spain, collaborated with de Arfe, not least on the tombs of Charles V and Philip II in the church of the Monastery of El Escorial, and it is tempting to imagine de Arfe and Leoni examining Leonardo’s drawings together. Scholars, however, date Leoni’s purchase of the drawings to 1589 and whether that date is correct or not, de Arfe does not cite Leonardo in his text, presenting a somewhat mysterious lacuna.

‘Libro Tercero: Trata de las Alturas y Formas de Los Animales y Aves’ with its depictions of animals in part I and birds in part II, includes clear copies from Conrad Gessner’s ‘Historia Animalium’, the camel and dromedary, the donkey, the ostrich and Dürer’s rhinoceros being the most obvious, and other sources such as the various illustrated editions of Pliny. The final book, ‘Libro Quarto, Trata de Architectura, y Pieças de Iglesia’, demonstrates, in the first part, de Arfe’s absorption of and familiarity with Serlio (see Maria del Carmen Heredia Moreno’s ‘Juan de Arfe Villafañe y Sebastiano Serlio’ for an extensive analysis), in particular Serlio's ‘Book IV (‘Regole Generali di Architectura Sopre le Cinque Maniere … &c.’) of 1537 together with the works of Vignola, Labacco and Vitruvius, all of which de Arfe is known to have owned. Like Serlio (and Vignola), de Arfe analyses the five Classical orders, detailing and depicting their coherent elements, and adding his own ‘Attic’ order, but it is in his introduction, with its history of architecture from Classical times to the more specific, and to him familiar, Spanish architecture of the previous centuries that de Arfe enumerates his peers. de Arfe cites Vitruvius, Andronicus of Cyrrhus, both his father and grand-father as well as Bramante, Alonso de Covarrubias, Baldassare Peruzzi (Baltazar Petrussio) and Leon Battista Alberti, whose ‘De Re Aedificatoria’ had been translated - by de Arfe’s friend Zamorano - and published in Spanish in 1582.

Alberti, and Zamorano’s important 1582 translation, are both crucial for the second part of de Arfe’s ‘Libro Quatro’, the section ‘De las Pieças de Iglesia’, considered to be both the most important and the most original section of the treatise. Moving from the theoretical to the practical, de Arfe demonstrates with the use of examples, architectural usage and ecclesiastical sculpture and ornament from the time of Pope Urban I onward to de Arfe’s day, detailing the proportions not only of the exterior and interior architecture and features of the church, but also, in detail, of the - in Spanish - ‘Caliz, Portapaz, Candelero, Cruz portatil, Agua manil y Fuente, Baculo’, the ‘Cruz, Encensario, Sceptro’, ‘Blandon, Lampada’ and the ‘Custodia de assent’ and ‘Custodia portatil’. Among the detailed woodcuts of examples, de Arfe includes work of his own, and other work, perhaps unidentified or theoretical or archetypical in nature.

de Arfe’s ‘De Varia Commensuracion’ is composed as follows:

I. Libro Primero, Trata de las Figuras Geométricas y Cuerpos Regulares è Irregulares, con los Cortes de Sus Laminas, los Relojes Horizontales, Cilindros, y Annulos: (i) De los Lineas; (ii) De los Cuerpos.

II. Libro Segundo, Trata de la Proporcion y Medida Particular de los Miembros del Cuerpo Humano, con sus Huesos y Morcillas, y los Escorços de Sus Partes: (i) De la Medida; (ii) De los Huesos; (iii) De los Morzillas del Cuerpo; (iv) De los Escorcos.

III. Libro Tercero, Trata de las Alturas y Formas de los Animales y Aves: (i) De los Animales de Quatro Pies; (ii) De los Aves.

IV: Libro Quarto, Trata de Architectura, y Pieças de Iglesia: (i) De las Lineos Ordenes; (ii) De las Pieças de Iglesia.

’This pioneering and richly illustrated treatise on science and theoretical knowledge applicable to the visual arts included four books on geometry, anatomy, zoology and architecture, of which the ‘Libro segundo’ is a rare and unique source produced by an anatomically trained artist of the late Spanish Renaissance.’ (Bjørn Okholm Skaarup).

‘Juan de Arfe y Villafañe, who was appointed by Philip II, Master of the Mint at Segovia, published a treatise on his art, with exact designs for every piece of church-plate, and his elegant models have fortunately been generally adopted and continued. This work, which every collector should purchase, is entitled ‘De Varia Commensuracion’; it has gone through many editions. Those now before us are, first, that of Seville, 1585, by Andrea Pescioni; and Villafañe was fortunate in securing for his printer this Italian, who had a kindred soul, and whose works are among the few in Spain which can be really called artistically.’ (Richard Ford).

‘In the late sixteenth century, one of the most advanced manuals on art didactics in Europe was the Varia commensuración para la Esculptura y Architectura (1585-1587) by the Spanish silver and goldsmith, artisan and sculptor Juan de Arfe y Villafañe … During the sixteenth century, there were only two printed treatises for artists which contained chapters on artistic anatomy: Libro segundo (1585) by Arfe and Livre de pourtraiture (1595) by Jean Cousin … The whole text of the Varia suggests that Arfe saw himself as the creator of a new sort of teaching manual, the one who took Spanish art and the reputation of artists on a higher intellectual level – and, indeed, that was true … It was the genius of the Spanish artist Arfe y Villafañe that conceived a new and logically structured manual on drawing the human figure, compiled from older pictorial material. Libro segundo of the Varia is a pivotal contribution to European art didactical literature.’ (Boris Röhrl).

'Juan de Arfe's design for the main tabernacle, or 'custodia', in the cathedral of Seville (1580 - 1587) was illustrated by him in his 'De Varia Commensuración para la Escultura y Architectura'. Arfe successfully appropriated the status of architecture for the 'custodia', establishing the strong Spanish 'connection between architecture and metalworking' ... His architectonic emphasis successfully counters the criticism implicit in the term 'plateresque', ascribed since the seventeenth century to Renaissance architectural decoratin influenced by silverwork.' (Millard).

‘He [de Arfe] studied anatomy in Salamanca and Toledo, at the former city under Cosme de Medina. In Toledo he attempted to establish the proportions of the human body … Arphe belongs to those Spanish artists who spent much time on an earnest study of anatomy, as Alonson Berreguette (1480 - 1561) and Gaspar Becerra (1520 - 1570) … They were also particularly interested in the study of the proportions of the human body and also made use of Albrecht Dürer’s (1471 - 1528) work on proportions … ‘. (Ludwig Choulant).

Books I, II and IV of ’De Varia Commensuracion’ are dated 1585, however Book II is dated 1587 and it is not clear, as each Book has a discrete title and separate foliation and collation, whether parts were issued before the whole work. The woodcut for the colophon of the first two books features the motto ‘PEU A PEU’ which is absent from those of the two final books, while the inclusion of the ‘Tabla’ for Book III with that of Book IV does suggest they were issued at the same time; whether this was due to an interruption in the printing, a dispute regarding the ‘Licencia’ or for another reason is unknown. This copy, as for several other known examples, features de Arfe’s signature to the foot of the title together with another barely distinguishable name (attempts have been made to efface both) suggesting that it may have been a presentation copy.

‘De Varia Commensuracion’ is scarce in any edition and this, the first edition, is of particular rarity. A note in Italian to the front free endpaper attests to this: ‘Il Cicognara aveva un Edizione de’ Madrid in fol. del 1730 / che annunzia per rara. Questa del 1585 che / può dizia Editio Princeps è introvabile’. We can trace a single copy at auction in the last century, while COPAC lists only the copy at the V & A (the British Library holds a copy, however, the catalogue lists it as two parts only); OCLC adds an additional copy in the UK at the Wellcome (incomplete, 3 parts only), two copies in Spain and France, a copy at Frankfurt and one at Utrecht. In the US, only Harvard appears to hold a copy, described as mutilated and lacking text, although the Library of Congress once owned a copy of the treatise (it does not appear in the present catalogue). It is not clear from the 1830 catalogue - it is listed in the sub-section 'Gardening, Painting, Sculpture' of 'Fine Arts' without author or date - which edition it was.

[not in Millard (but see pg. 426); not in RIBA (1773 Madrid 6th ed. only); not in Cicognara (1736 Madrid 4th ed. only); not in Fowler (1773 Madrid 6th ed. only); not in Berlin (1763 Madrid 5th ed.); not in Brunet (1589 Madrid 2nd ed. only); not in Park; see RIchard Ford’s 'A Handbook for Traveller's in Spain and Readers at Home', vol. 2, pg. 634; see Bjørn Okholm Skaarup’s ’Anatomy for the Artist … &c.’ in ‘Anatomy and Anatomists in Early Modern Spain’, Farnham, 2015, pp. 246 - 256; see Maria del Carmen Heredia Moreno’s ‘Juan de Arfe Villafañe y Sebastiano Serlio’, 2003; see Ludwig Choulant’s ‘History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration in Its Relation to Anatomic Science and the Graphic Arts’, Chicago, 1920, pp. 218 - 221; see Boris Röhrl’s ‘Leonardo da Vinci’s Anatomical Drawings and Juan de Arfe y Villafañe’, in Archivo Español de Arte, Vol. 87 (346), 2014, pp. 139 - 156].

'The most comprehensive Spanish sixteenth-century work on sculpture and architecture is that by Juan de Arfe y Villafañe ... '. (Hanno-Walter Kruft).

Juan de Arfe y Villafañe (Leon 1535 - Madrid 1600) was the son and grand-son of artists, an accomplished sculptor, anatomically-trained artist, metal-worker and architect, not to mention a highly important and influential theorist. de Arfe’s first major printed work ‘Quilatador de la Plata, Oro, y Piedras’ of 1572, is a notable text on the assay of metals (in particular silver and gold) and the valuation and assessment of gems, however, it is this later work of 1585, the ‘De Varia Commensuracion para la Esculptura, y Architectura’, with its debts - acknowledged or not - to Leonardo, Serlio, Dürer and Vasari that ensured his enduring legacy as the ’Spanish Cellini’. Divided into four books, each again divided into sub-sections (see below), the ‘De Varia Commensuracion’ is an artistic and scientific tour de force that marks de Arfe as an emblematic figure of the Spanish Renaissance. Richard Ford described de Arfe as ‘the greatest artist of his family’ and ‘the Bezaleel of the Peninsula’ (after Moses’ artisan of the Tabernacle and overseer of the making of the Ark of the Covenant) and ‘the Cellini of Spaniards’.

Each of de Arfe’s four books demonstrate his credentials as a pioneering Renaissance figure: his familiarity with the works of Euclid (translated into Spanish by de Arfe’s contemporary and friend Rodrigo Zamorano) is demonstrated in his ‘Libro Primero: Trata de las Figuras Geometricas &c.’, and his familiarity with navigation is demonstrated by a series of mathematical / navigational tables relating to Spain and her surrounds, astronomical instruments, their uses and so on. The ‘Libro Secundo: Trate de la Proporcion’ is indebted not only to Dürer and his ‘Hierin sind Begriffen vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion’ (1528) but also to the anatomical drawings of Leonardo. In a series of woodcut plates, de Arfe delineates the body, ‘representing outlines of the whole body or of single parts with the measurements’ (Choulant) including the body of a woman - de Arfe describes the essentials for a beautiful female body - and the proportions for a child. The affinities between de Arfe’s woodcuts and Leonardo are clear, however, what is less clear is their transmission. It is known that Pompeo Leoni acquired the majority of Leonardo’s writings and drawings, or at least those left to his father, Francesco, from Orazio Melzi in the 1580s while Leoni had a studio in Madrid. Leoni, working for successive Kings of Spain, collaborated with de Arfe, not least on the tombs of Charles V and Philip II in the church of the Monastery of El Escorial, and it is tempting to imagine de Arfe and Leoni examining Leonardo’s drawings together. Scholars, however, date Leoni’s purchase of the drawings to 1589 and whether that date is correct or not, de Arfe does not cite Leonardo in his text, presenting a somewhat mysterious lacuna.

‘Libro Tercero: Trata de las Alturas y Formas de Los Animales y Aves’ with its depictions of animals in part I and birds in part II, includes clear copies from Conrad Gessner’s ‘Historia Animalium’, the camel and dromedary, the donkey, the ostrich and Dürer’s rhinoceros being the most obvious, and other sources such as the various illustrated editions of Pliny. The final book, ‘Libro Quarto, Trata de Architectura, y Pieças de Iglesia’, demonstrates, in the first part, de Arfe’s absorption of and familiarity with Serlio (see Maria del Carmen Heredia Moreno’s ‘Juan de Arfe Villafañe y Sebastiano Serlio’ for an extensive analysis), in particular Serlio's ‘Book IV (‘Regole Generali di Architectura Sopre le Cinque Maniere … &c.’) of 1537 together with the works of Vignola, Labacco and Vitruvius, all of which de Arfe is known to have owned. Like Serlio (and Vignola), de Arfe analyses the five Classical orders, detailing and depicting their coherent elements, and adding his own ‘Attic’ order, but it is in his introduction, with its history of architecture from Classical times to the more specific, and to him familiar, Spanish architecture of the previous centuries that de Arfe enumerates his peers. de Arfe cites Vitruvius, Andronicus of Cyrrhus, both his father and grand-father as well as Bramante, Alonso de Covarrubias, Baldassare Peruzzi (Baltazar Petrussio) and Leon Battista Alberti, whose ‘De Re Aedificatoria’ had been translated - by de Arfe’s friend Zamorano - and published in Spanish in 1582.

Alberti, and Zamorano’s important 1582 translation, are both crucial for the second part of de Arfe’s ‘Libro Quatro’, the section ‘De las Pieças de Iglesia’, considered to be both the most important and the most original section of the treatise. Moving from the theoretical to the practical, de Arfe demonstrates with the use of examples, architectural usage and ecclesiastical sculpture and ornament from the time of Pope Urban I onward to de Arfe’s day, detailing the proportions not only of the exterior and interior architecture and features of the church, but also, in detail, of the - in Spanish - ‘Caliz, Portapaz, Candelero, Cruz portatil, Agua manil y Fuente, Baculo’, the ‘Cruz, Encensario, Sceptro’, ‘Blandon, Lampada’ and the ‘Custodia de assent’ and ‘Custodia portatil’. Among the detailed woodcuts of examples, de Arfe includes work of his own, and other work, perhaps unidentified or theoretical or archetypical in nature.

de Arfe’s ‘De Varia Commensuracion’ is composed as follows:

I. Libro Primero, Trata de las Figuras Geométricas y Cuerpos Regulares è Irregulares, con los Cortes de Sus Laminas, los Relojes Horizontales, Cilindros, y Annulos: (i) De los Lineas; (ii) De los Cuerpos.

II. Libro Segundo, Trata de la Proporcion y Medida Particular de los Miembros del Cuerpo Humano, con sus Huesos y Morcillas, y los Escorços de Sus Partes: (i) De la Medida; (ii) De los Huesos; (iii) De los Morzillas del Cuerpo; (iv) De los Escorcos.

III. Libro Tercero, Trata de las Alturas y Formas de los Animales y Aves: (i) De los Animales de Quatro Pies; (ii) De los Aves.

IV: Libro Quarto, Trata de Architectura, y Pieças de Iglesia: (i) De las Lineos Ordenes; (ii) De las Pieças de Iglesia.

’This pioneering and richly illustrated treatise on science and theoretical knowledge applicable to the visual arts included four books on geometry, anatomy, zoology and architecture, of which the ‘Libro segundo’ is a rare and unique source produced by an anatomically trained artist of the late Spanish Renaissance.’ (Bjørn Okholm Skaarup).

‘Juan de Arfe y Villafañe, who was appointed by Philip II, Master of the Mint at Segovia, published a treatise on his art, with exact designs for every piece of church-plate, and his elegant models have fortunately been generally adopted and continued. This work, which every collector should purchase, is entitled ‘De Varia Commensuracion’; it has gone through many editions. Those now before us are, first, that of Seville, 1585, by Andrea Pescioni; and Villafañe was fortunate in securing for his printer this Italian, who had a kindred soul, and whose works are among the few in Spain which can be really called artistically.’ (Richard Ford).

‘In the late sixteenth century, one of the most advanced manuals on art didactics in Europe was the Varia commensuración para la Esculptura y Architectura (1585-1587) by the Spanish silver and goldsmith, artisan and sculptor Juan de Arfe y Villafañe … During the sixteenth century, there were only two printed treatises for artists which contained chapters on artistic anatomy: Libro segundo (1585) by Arfe and Livre de pourtraiture (1595) by Jean Cousin … The whole text of the Varia suggests that Arfe saw himself as the creator of a new sort of teaching manual, the one who took Spanish art and the reputation of artists on a higher intellectual level – and, indeed, that was true … It was the genius of the Spanish artist Arfe y Villafañe that conceived a new and logically structured manual on drawing the human figure, compiled from older pictorial material. Libro segundo of the Varia is a pivotal contribution to European art didactical literature.’ (Boris Röhrl).

'Juan de Arfe's design for the main tabernacle, or 'custodia', in the cathedral of Seville (1580 - 1587) was illustrated by him in his 'De Varia Commensuración para la Escultura y Architectura'. Arfe successfully appropriated the status of architecture for the 'custodia', establishing the strong Spanish 'connection between architecture and metalworking' ... His architectonic emphasis successfully counters the criticism implicit in the term 'plateresque', ascribed since the seventeenth century to Renaissance architectural decoratin influenced by silverwork.' (Millard).

‘He [de Arfe] studied anatomy in Salamanca and Toledo, at the former city under Cosme de Medina. In Toledo he attempted to establish the proportions of the human body … Arphe belongs to those Spanish artists who spent much time on an earnest study of anatomy, as Alonson Berreguette (1480 - 1561) and Gaspar Becerra (1520 - 1570) … They were also particularly interested in the study of the proportions of the human body and also made use of Albrecht Dürer’s (1471 - 1528) work on proportions … ‘. (Ludwig Choulant).

Books I, II and IV of ’De Varia Commensuracion’ are dated 1585, however Book II is dated 1587 and it is not clear, as each Book has a discrete title and separate foliation and collation, whether parts were issued before the whole work. The woodcut for the colophon of the first two books features the motto ‘PEU A PEU’ which is absent from those of the two final books, while the inclusion of the ‘Tabla’ for Book III with that of Book IV does suggest they were issued at the same time; whether this was due to an interruption in the printing, a dispute regarding the ‘Licencia’ or for another reason is unknown. This copy, as for several other known examples, features de Arfe’s signature to the foot of the title together with another barely distinguishable name (attempts have been made to efface both) suggesting that it may have been a presentation copy.

‘De Varia Commensuracion’ is scarce in any edition and this, the first edition, is of particular rarity. A note in Italian to the front free endpaper attests to this: ‘Il Cicognara aveva un Edizione de’ Madrid in fol. del 1730 / che annunzia per rara. Questa del 1585 che / può dizia Editio Princeps è introvabile’. We can trace a single copy at auction in the last century, while COPAC lists only the copy at the V & A (the British Library holds a copy, however, the catalogue lists it as two parts only); OCLC adds an additional copy in the UK at the Wellcome (incomplete, 3 parts only), two copies in Spain and France, a copy at Frankfurt and one at Utrecht. In the US, only Harvard appears to hold a copy, described as mutilated and lacking text, although the Library of Congress once owned a copy of the treatise (it does not appear in the present catalogue). It is not clear from the 1830 catalogue - it is listed in the sub-section 'Gardening, Painting, Sculpture' of 'Fine Arts' without author or date - which edition it was.

[not in Millard (but see pg. 426); not in RIBA (1773 Madrid 6th ed. only); not in Cicognara (1736 Madrid 4th ed. only); not in Fowler (1773 Madrid 6th ed. only); not in Berlin (1763 Madrid 5th ed.); not in Brunet (1589 Madrid 2nd ed. only); not in Park; see RIchard Ford’s 'A Handbook for Traveller's in Spain and Readers at Home', vol. 2, pg. 634; see Bjørn Okholm Skaarup’s ’Anatomy for the Artist … &c.’ in ‘Anatomy and Anatomists in Early Modern Spain’, Farnham, 2015, pp. 246 - 256; see Maria del Carmen Heredia Moreno’s ‘Juan de Arfe Villafañe y Sebastiano Serlio’, 2003; see Ludwig Choulant’s ‘History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration in Its Relation to Anatomic Science and the Graphic Arts’, Chicago, 1920, pp. 218 - 221; see Boris Röhrl’s ‘Leonardo da Vinci’s Anatomical Drawings and Juan de Arfe y Villafañe’, in Archivo Español de Arte, Vol. 87 (346), 2014, pp. 139 - 156].

[148 leaves; foliated at upper right with occasional misfoliation: (6), 35, (1); 48, (2); 14; 40, (2)]. Collation: §6, A6 - F6; a6 - g6 (e missigned c), h8; Aa8, Bb6; Aaa6 - Ggg6. Small folio. (316 x 218 mm). Printed title with elaborate woodcut arms of the dedicatee, Pedro Giron, Duke of Ossuna (Osuna), verso with oval vignette portrait of the author and dedicatory sonnet by Luis de Torquemada, leaf with 'Licencia' dated December 24th, 1584 recto and de Arfe's dedication to the Duke of Osuna verso, two leaves with 'A los Lectores' and 'Carmen', two leaves with 'Prologo' and 'Libro Primero' to 'Libro Quarto' of de Arfe's text (with his mnemonic verse) illustrated with 285 woodcuts (235 vignettes keyed to the text and 50 full-page plates, mathematical tables in Book I, Part II), de Arfe's woodcut arms to title of each Book, woodcut tail-piece to conclusion of each Book, 'Tabla' for Books I and II at conclusion of each, those for Book III and IV at the conclusion of Book IV, printed text in Spanish in italic and roman types throughout. Occasional annotations in sepia ink in an early hand, some minor soiling and staining, occasional repairs with no loss, marginal repairs to outer margins of final four leaves. Later Italian (?) thick interim card wrappers, manuscript titles to spine in sepia.

#47216