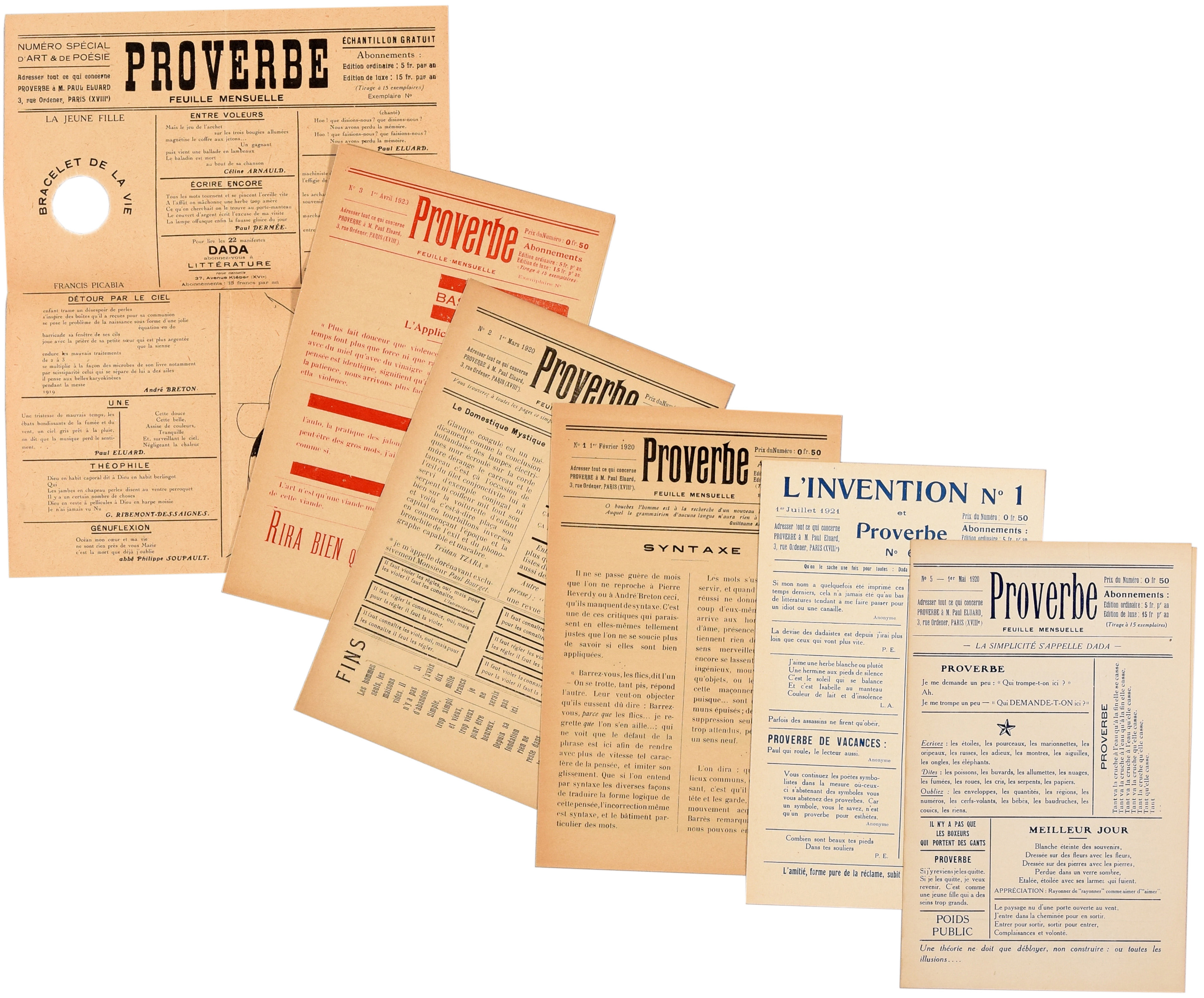

Proverbe. Feuille Mensuelle. Nos. 1 (1er Février 1920) - 5 (1er Mai 1920) + No. 6 (Also L'Invention 1, 1er Juillet 1921). (All Published)

Proverbe. Eluard, Paul (Ed.)

Paris. 1920–1921

A rare complete and unsophisticated set of this Paris dada periodical.

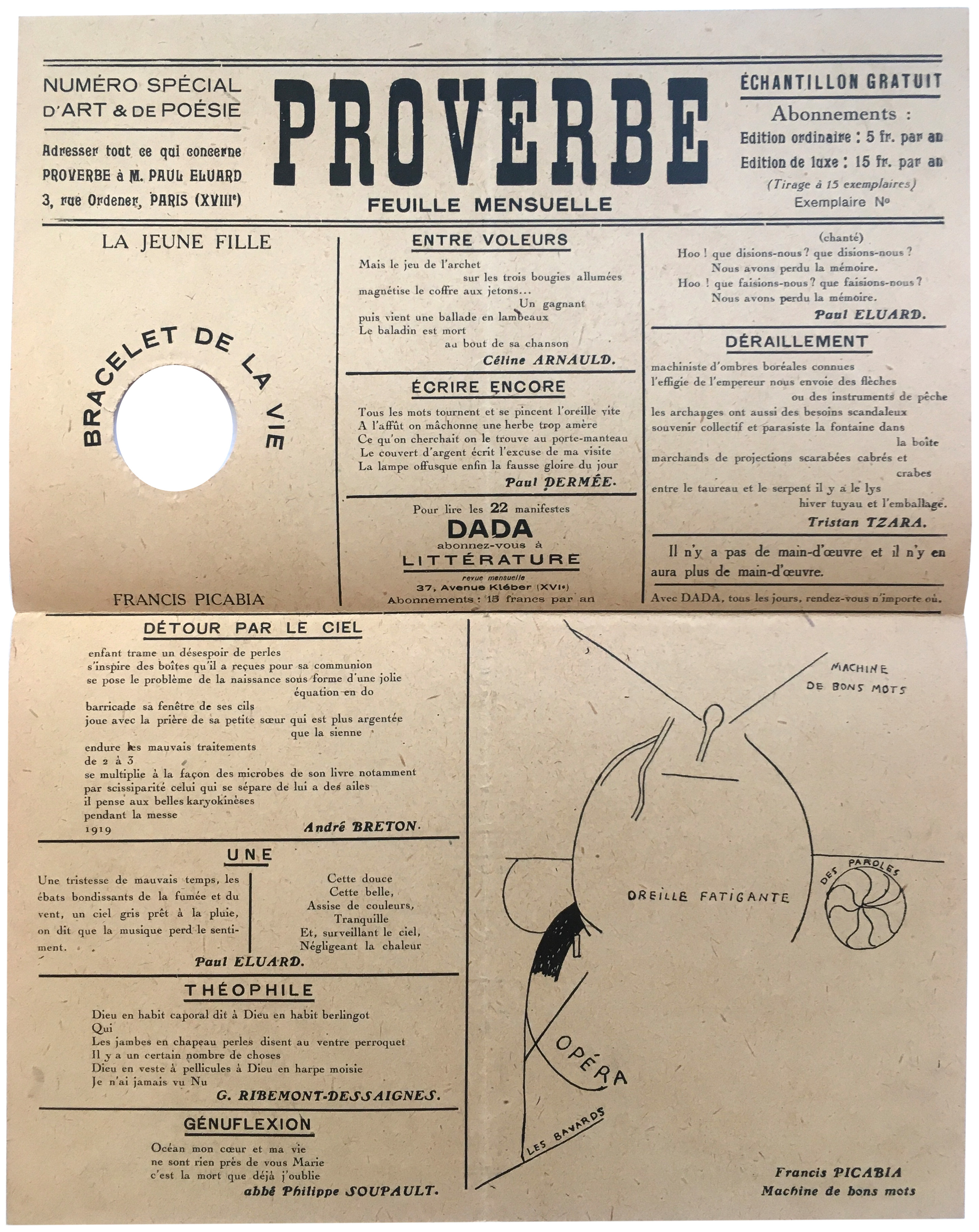

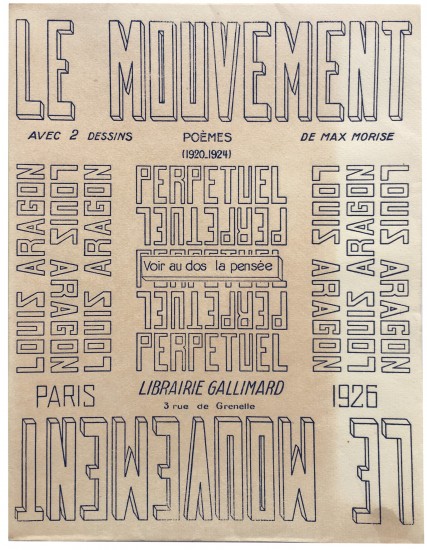

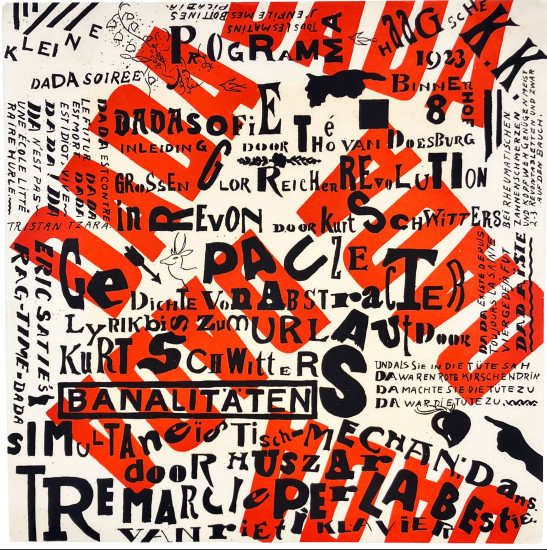

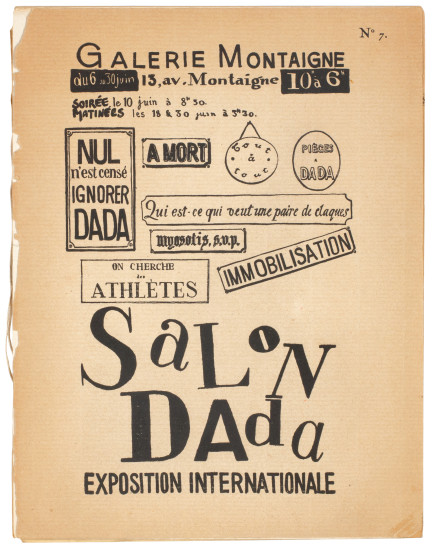

Edited by poet Paul Eluard, the focus of 'Proverbe' is far more seriously linguistic, although it retains the playfulness to be expected from dada, than many other periodicals of the period. Although the typical elements of dada typography are present - the variable font, different register, differing colours, the ruling and the use of different angles of printing to the plane of the page - here it is the word that reigns. In fact, only one of the issues is in any sense illustrated: issue 4 contains a reproduction of a drawing by Picabia, the 'Machine de bon mots', but even here Picabia's concern is at least as semantic as visual.

The first article of the first issue makes the aim of 'Proverbe' clear: 'Syntaxe' by Jean Paulhan with its urge to reinvigorate language is followed by pieces by Phillipe Soupault, Tristan Tzara, an aperçu by the Marquis de Sade and an editorial page of aphorisms, mottoes, advertisements and instructions. Perhaps the most memorable of these latter is the reassuring announcement concerning Picabia's '391': '391 ne contient pas d'arsenic. On peut le prendre en toute sécurité et en secret sans rien changer à ses habitudes.'

The second issue saw the arrival of additional contributors and the editorial board of Louis Aragon, André Breton, Paul Eluard, Jean Paulhan, Francis Picabia, Maurice Raynal and Philippe Soupault was expanded to include Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. Issue 4 - the only illustrated issue - was printed on the recto only of the sheet but with an excised circular hole (Picabia again) incorporated into the issue and titled 'Bracelet de la Vie'.

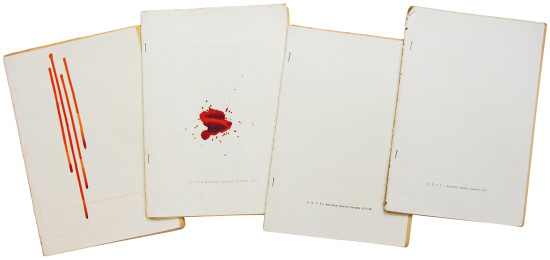

The contributions for issue five were published anonymously while issue 6, printed after a delay of nearly a year, was titled additionally 'L'Invention' and gives only the initials (readily identifiable) of each of the contributors. On the final page of issue 6 the contributors are listed as: 'la Canule de verre, Rides propres, la Nourrice des étoiles, le Grand serpent de terre, le Mandarin citron, l'Homme à vapeur, la Pissotière à musique et l'Homme à la tête de perle'.

'Je m'appelle maintenant tu. Tzara, fou, vierge. / Tristan Tzara est un idiote vierge. Francis Picabia. / Et il n'y aura jamais de faux Dada. Paul Eluard.' (Proverbe No. 3, 1920).

' ... a delicious melange of quotations from Picabia, Paulhan, Aragon, Dermée and others ... '. (Ex-Libris Cat. 2).

Edited by poet Paul Eluard, the focus of 'Proverbe' is far more seriously linguistic, although it retains the playfulness to be expected from dada, than many other periodicals of the period. Although the typical elements of dada typography are present - the variable font, different register, differing colours, the ruling and the use of different angles of printing to the plane of the page - here it is the word that reigns. In fact, only one of the issues is in any sense illustrated: issue 4 contains a reproduction of a drawing by Picabia, the 'Machine de bon mots', but even here Picabia's concern is at least as semantic as visual.

The first article of the first issue makes the aim of 'Proverbe' clear: 'Syntaxe' by Jean Paulhan with its urge to reinvigorate language is followed by pieces by Phillipe Soupault, Tristan Tzara, an aperçu by the Marquis de Sade and an editorial page of aphorisms, mottoes, advertisements and instructions. Perhaps the most memorable of these latter is the reassuring announcement concerning Picabia's '391': '391 ne contient pas d'arsenic. On peut le prendre en toute sécurité et en secret sans rien changer à ses habitudes.'

The second issue saw the arrival of additional contributors and the editorial board of Louis Aragon, André Breton, Paul Eluard, Jean Paulhan, Francis Picabia, Maurice Raynal and Philippe Soupault was expanded to include Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. Issue 4 - the only illustrated issue - was printed on the recto only of the sheet but with an excised circular hole (Picabia again) incorporated into the issue and titled 'Bracelet de la Vie'.

The contributions for issue five were published anonymously while issue 6, printed after a delay of nearly a year, was titled additionally 'L'Invention' and gives only the initials (readily identifiable) of each of the contributors. On the final page of issue 6 the contributors are listed as: 'la Canule de verre, Rides propres, la Nourrice des étoiles, le Grand serpent de terre, le Mandarin citron, l'Homme à vapeur, la Pissotière à musique et l'Homme à la tête de perle'.

'Je m'appelle maintenant tu. Tzara, fou, vierge. / Tristan Tzara est un idiote vierge. Francis Picabia. / Et il n'y aura jamais de faux Dada. Paul Eluard.' (Proverbe No. 3, 1920).

' ... a delicious melange of quotations from Picabia, Paulhan, Aragon, Dermée and others ... '. (Ex-Libris Cat. 2).

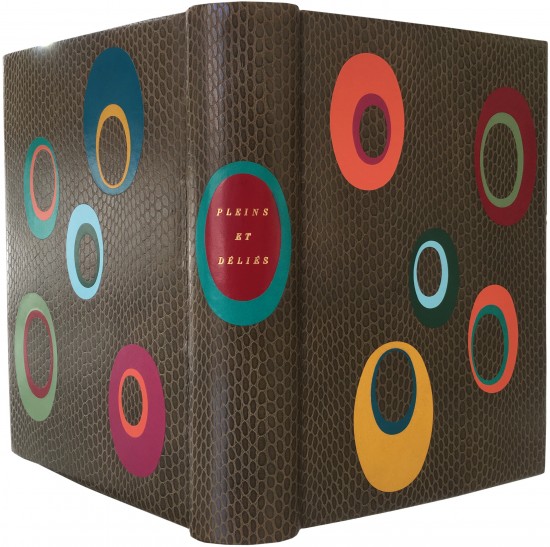

[Single folded sheets of newspaper stock; issue 3 printed in red, issue 4 printed vertically with no outer text]. 6 issues. (221 x 139 mm). Issue no. 4 with a printed illustration 'Machine de bon mots' after a drawing by Francis Picabia and the printed stamp in red on outer unprinted wrapper: 'PROVERBE / n'existe que pour / justifier les mots.' Single printed folded sheets as issued.

#47900