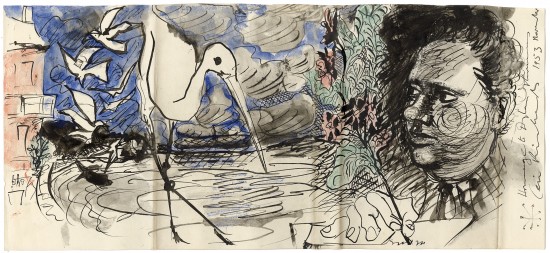

Original Futurist Drawing Executed on the Verso of A Photograph of Nevinson With His Ambulance in WWI

Nevinson, Christopher Richard Wynne

(Malo-les-Bains). 1915

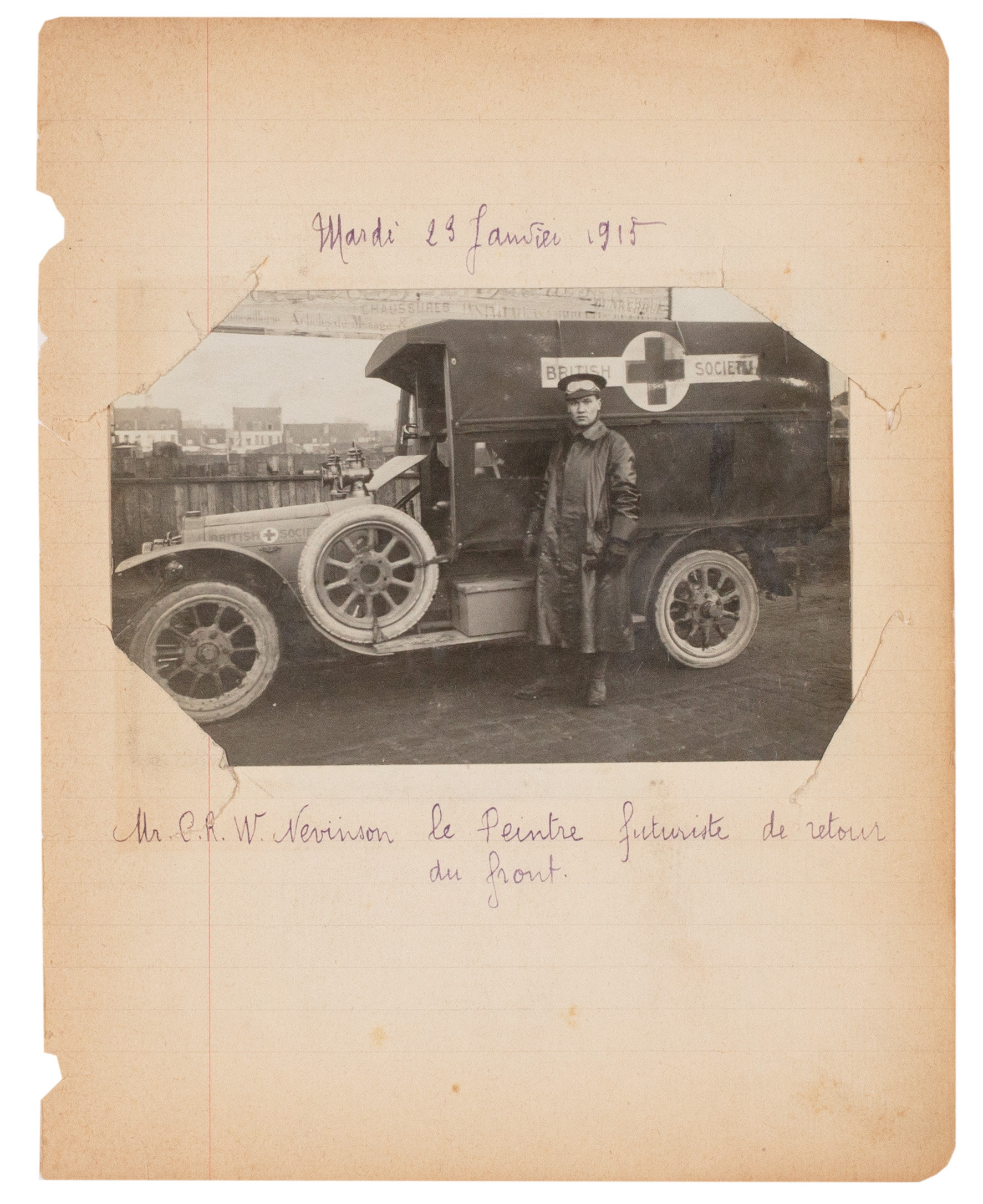

An extraordinary Futurist drawing by Nevinson from the First World War executed on the verso of the rare photograph of Nevinson standing beside his Friends' Ambulance Unit Mors Motor 'bus'.

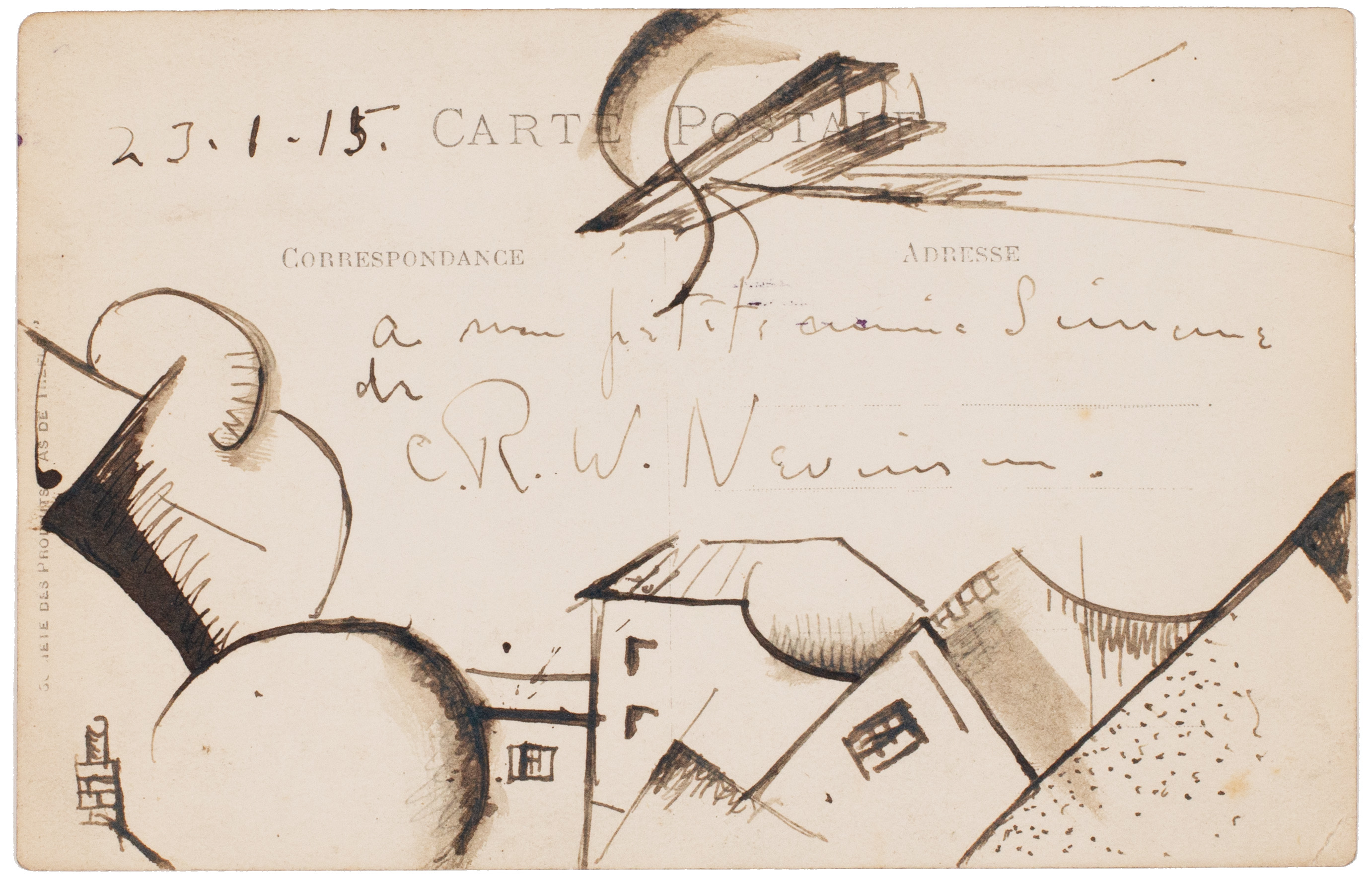

Nevinson's original Futurist drawing depicts a fighter aircraft, a biplane, above a townscape of roofs and chimneys with what appears to be billowing smoke or clouds; his presentation - like his drawing - is in sepia ink: '23.1.15. / a [sic] mon petite amie Simone / de / C. R. W. Nevinson.'

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889 - 1946) volunteered for service with the Red Cross as an ambulance driver at the declaration of war in 1914 (Nevinson was born with a limp and would not have passed the physical examination for the army), 'pursued by the urge to do something'. He was attached to a unit of the Friends' Ambulance Service and on arrival at Dunkirk was immersed immediately in the horrors of 'The Shambles', the nickname for the shed 'full of dead, wounded, and dying' that was the result of the near complete collapse of French medical service. After the institution of the Lady Florence Fiennes Hospital at Malo-les-Bains, Nevinson ferried the wounded from 'The Shambles', and from the front at Woosten and Ypres, to the hospital for treatment. After Nevinson's leg began to make driving too difficult he was retained at Malo-les-Bains as nurse where he remained until his return to England at the end of January 2015.

The recipient of the present drawing and photograph was Sister Simone Lengrand, a nurse at the Lady Florence Fiennes Hospital (the dearth of adequate medical facilities in the early part of the war saw the establishment of private hospitals funded by philanthropic individuals or societies), who must have known Nevinson through their work at the hospital. Nevinson commissioned this photograph, of the artist beside his 'bus', a Mors Motor ambulance, and sent another example to Marinetti, now held at the Palazzo Grassi. Although the reasons for Nevinson's departure from France are unknown - Nevinson suggests he was invalided home - he was certainly back in London very shortly after this drawing was executed and presented. Nevinson exhibited compositions inspired directly by his experiences in March 1915 before he volunteered for service with the Royal Army Medical Corps in London; he was commissioned as an official war artist in 1917.

Nevinson often created small drawings that he used later as the basis for larger and more elaborate paintings and several examples of such war drawings are known. Although no painting is known after the present drawing, its presentation mitigates against this in any case, it does include important elements of Nevinson's wider war oeuvre. The presence of a biplane - as per 'Paint and Prejudice', 'Dunkirk was one of the first towns to suffer aerial bombardment' - is remarkable and an image and motif that Nevinson returned to often in paintings (see 'Spiral Descent' of 1916 and 'Aerial View' from 1919 / 1920) and prints (see 'Swooping Down on a Taube', 'Banking at 4000 Feet' and 'In th Air', all 1917). The townscape too is itself noteable and is highly reminiscent of that of the 1915 painting 'Ypres After the First Bombardment' with its empty facades, absent rooves and billowing smoke. This drawing represents an important and hitherto unknown stage in Nevinson's artistic development from the period prior to the war to his later work as a war artist and is a crucial indicator that Nevinson continued to work as an artist while at the front.

The drawing and photograph remained in the collection of Simone Lengrand, she retained it together with all her memorabilia of the war in a memorial album of cuttings and photographs, until her death. The photograph was inserted loosely into a support sheet (it is retained here) with her note 'Mardi 23 Janvier 1915' (above) and 'Mr C. R. W. Nevinson le Peintre futuriste de / retour du front' (beneath). The verso of the photograph, and therefore the drawing itself, remained hidden until the sale of the album; the album has been dispersed and is not present here.

'By the time I had been at The Shambles a week my former life seemed to be years away. When a month had passed I felt I had been born in the nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting that man seldom conceives them in his mind and there was no shrinking even among the more sensitive of us. We could only help, and ignore shrieks, puss, gangrene and the disembowelled.' (Nevinson writing in 'Paint and Prejudice').

'The problem for Richard [Nevinson[ was how to depict the war, how to identify a suitable compromise in subject matter and technique and how to isolate himself from the negativity surrounding extreme Futurist rhetoric, while retaining his avant-garde, and possibly, rebel, status. Beyond acceptability, Richard also had to wrestle with the concept of presenting this new, and very modern, though often visually mundane, war ... The colourful uniforms had been replaced with khaki, the heroic charges and defences with long-range shelling, the sweeping military manoeuvres with trench warfare. The era of the machine gun, the U-Boat, the aeroplane and poison gas was going to guarantee that this war would not be picturesque in the way that the conflicts had been depicted in the past. A new language would almost certainly be required to depict this most modern of wars; the first total war.' (Michael Walsh).

[see Nevinson's 'Paint and Prejudice', London, Methuen, 1937; see Michael Walsh's 'C. R. W. Nevinson: This Cult of Violence', New Haven and London, 2002].

Nevinson's original Futurist drawing depicts a fighter aircraft, a biplane, above a townscape of roofs and chimneys with what appears to be billowing smoke or clouds; his presentation - like his drawing - is in sepia ink: '23.1.15. / a [sic] mon petite amie Simone / de / C. R. W. Nevinson.'

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889 - 1946) volunteered for service with the Red Cross as an ambulance driver at the declaration of war in 1914 (Nevinson was born with a limp and would not have passed the physical examination for the army), 'pursued by the urge to do something'. He was attached to a unit of the Friends' Ambulance Service and on arrival at Dunkirk was immersed immediately in the horrors of 'The Shambles', the nickname for the shed 'full of dead, wounded, and dying' that was the result of the near complete collapse of French medical service. After the institution of the Lady Florence Fiennes Hospital at Malo-les-Bains, Nevinson ferried the wounded from 'The Shambles', and from the front at Woosten and Ypres, to the hospital for treatment. After Nevinson's leg began to make driving too difficult he was retained at Malo-les-Bains as nurse where he remained until his return to England at the end of January 2015.

The recipient of the present drawing and photograph was Sister Simone Lengrand, a nurse at the Lady Florence Fiennes Hospital (the dearth of adequate medical facilities in the early part of the war saw the establishment of private hospitals funded by philanthropic individuals or societies), who must have known Nevinson through their work at the hospital. Nevinson commissioned this photograph, of the artist beside his 'bus', a Mors Motor ambulance, and sent another example to Marinetti, now held at the Palazzo Grassi. Although the reasons for Nevinson's departure from France are unknown - Nevinson suggests he was invalided home - he was certainly back in London very shortly after this drawing was executed and presented. Nevinson exhibited compositions inspired directly by his experiences in March 1915 before he volunteered for service with the Royal Army Medical Corps in London; he was commissioned as an official war artist in 1917.

Nevinson often created small drawings that he used later as the basis for larger and more elaborate paintings and several examples of such war drawings are known. Although no painting is known after the present drawing, its presentation mitigates against this in any case, it does include important elements of Nevinson's wider war oeuvre. The presence of a biplane - as per 'Paint and Prejudice', 'Dunkirk was one of the first towns to suffer aerial bombardment' - is remarkable and an image and motif that Nevinson returned to often in paintings (see 'Spiral Descent' of 1916 and 'Aerial View' from 1919 / 1920) and prints (see 'Swooping Down on a Taube', 'Banking at 4000 Feet' and 'In th Air', all 1917). The townscape too is itself noteable and is highly reminiscent of that of the 1915 painting 'Ypres After the First Bombardment' with its empty facades, absent rooves and billowing smoke. This drawing represents an important and hitherto unknown stage in Nevinson's artistic development from the period prior to the war to his later work as a war artist and is a crucial indicator that Nevinson continued to work as an artist while at the front.

The drawing and photograph remained in the collection of Simone Lengrand, she retained it together with all her memorabilia of the war in a memorial album of cuttings and photographs, until her death. The photograph was inserted loosely into a support sheet (it is retained here) with her note 'Mardi 23 Janvier 1915' (above) and 'Mr C. R. W. Nevinson le Peintre futuriste de / retour du front' (beneath). The verso of the photograph, and therefore the drawing itself, remained hidden until the sale of the album; the album has been dispersed and is not present here.

'By the time I had been at The Shambles a week my former life seemed to be years away. When a month had passed I felt I had been born in the nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting that man seldom conceives them in his mind and there was no shrinking even among the more sensitive of us. We could only help, and ignore shrieks, puss, gangrene and the disembowelled.' (Nevinson writing in 'Paint and Prejudice').

'The problem for Richard [Nevinson[ was how to depict the war, how to identify a suitable compromise in subject matter and technique and how to isolate himself from the negativity surrounding extreme Futurist rhetoric, while retaining his avant-garde, and possibly, rebel, status. Beyond acceptability, Richard also had to wrestle with the concept of presenting this new, and very modern, though often visually mundane, war ... The colourful uniforms had been replaced with khaki, the heroic charges and defences with long-range shelling, the sweeping military manoeuvres with trench warfare. The era of the machine gun, the U-Boat, the aeroplane and poison gas was going to guarantee that this war would not be picturesque in the way that the conflicts had been depicted in the past. A new language would almost certainly be required to depict this most modern of wars; the first total war.' (Michael Walsh).

[see Nevinson's 'Paint and Prejudice', London, Methuen, 1937; see Michael Walsh's 'C. R. W. Nevinson: This Cult of Violence', New Haven and London, 2002].

(90 x 140 mm). Gelatine silver print on photograph postcard stock, printed postcard layout and detail in French verso, verso with original drawing and presentation in sepia ink by Nevinson.

#48716